Network Monitors Water Quality in Shale Gas Drilling Region

High-pressure injection of water, sand and chemicals that fracture

shale deposits deep underground to free trapped natural gas is

employed by drillers tapping the Marcellus shale beds, a geologic

deposit that stretches from central New

York to Virginia and contains gas believed

to be worth hundreds of billions

of dollars.

The process, called hydraulic fracturing,

or fracking, has raised concerns

about possible impacts on water quality.

Tightly held “shale gas” like that in

the Marcellus shale deposits accounted

for 14 percent of the U.S. natural gas

supply in 2009, according to the U.S.

Energy Information Administration,

which expects the figure to grow to

45 percent of the nation’s gas by 2035

if current trends and policies remain

in place.

Hydraulic fracturing has been

practiced since 1949 and has become

extremely popular across the U.S. as gas

companies have increasingly focused

on hard-to-tap gas reserves, but little

information is available on its impact

on surface and ground water supplies.

The Susquehanna River Basin Commission

(SRBC), based in Harrisburg,

Penn., has established a 50-station

remote water quality monitoring network

to provide continuous, real-time

data on local streams and rivers in an

effort to determine whether fracking is

impacting water quality in the basin.

“There’s a lot of misinformation

and questions about transparency regarding

what’s happening out there in

the real world as far as Marcellus gas

drilling,” says Tom Beauduy, Deputy

Executive Director of the SRBC. “This

monitoring network provides an excellent opportunity to provide

the public with real data, and to serve as a sentinel for conditions

out there.”

Water-Intensive Process

To tap into shale gas in the Marcellus deposits, gas companies

drill vertical wells 5,000 to 9,000 feet deep, then turn their bits

horizontally for another 3,000 to 10,000 feet to maximize the

amount of shale each wellhead can reach. Steel casing surrounded

by cement is designed to isolate the well

from groundwater as the shaft travels

deep into the bedrock. When the well is

complete, explosive charges are pushed

to the horizontal portions of the well to

breach the casing and begin the fracturing

process. After the initial cracks

are made in the brittle shale, fracturing

fluid is pumped down the well at

high pressure to further pry open the

bedrock and free the gas.

Hydraulic fracturing is a waterintensive

process—3 to 5 million

gallons of frac fluid are typically used

to fracture the deposits reached by an

individual well. Of that solution, more

than 90 percent is water. Sand, which

props open the fissures in the fractured

deposit, comprises about 9 percent

of the mix. Each drilling company’s

proprietary blend of other ingredients,

which can range from mineral oil

lubricants to pH adjustors to biocides,

makes up the rest, accounting for 0.5

to 2 percent of the volume, according

to the U.S. Environmental Protection

Agency (EPA).

Most of the known ingredients in

frac fluid are relatively benign, notes

EPA, including products like mineral

oil, guar gum and citric acid. However,

others such as diesel fuel, ethylene

glycol, and the biocide glutaraldehyde

can present a significant environmental

concern—in the Marcellus wells, up to

10 percent of the frac fluid returns to

the surface within 30 days of injection

as “flowback.”

As many as 400 trucks serve a well during the fracturing process,

hauling frac fluid and produced water to and from the drill

pad. Wastewater ponds may also be constructed for temporary

storage. Both raise concerns over the danger of spills into local

streams, notes Andrew Gavin, Manager of SRBC’s Monitoring

and Protection Program.

Designing the Network

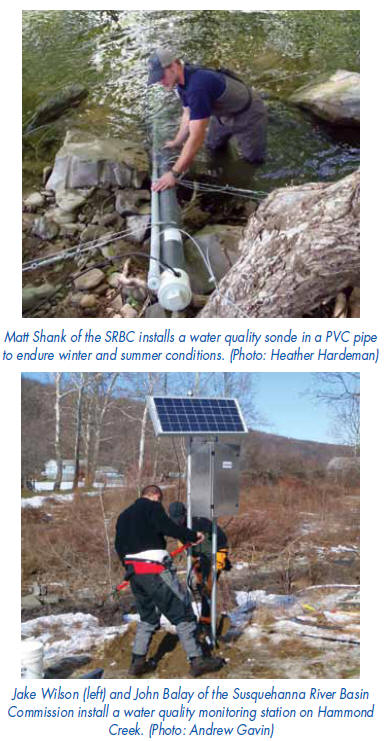

Building on SRBC’s experience with a drinking water quality

monitoring network established almost a decade ago, Gavin and

his colleagues developed a plan to deploy sondes—rugged probes

that collect and transmit information on water quality—for longterm,

continuous monitoring at 50 sites in the Susquehanna basin

where it overlies Marcellus shale in Pennsylvania and New York.

Each station consists of a YSI 6600 V2-4 multiparameter

sonde in a protective PVC housing tethered to the streambank

and connected to a data platform. Dataloggers are connected to

cell modems—or if a cell signal is unavailable, a satellite transmitter—

and powered by a solar panel.

Drillers have to disclose the contents of their long-secret

frac fluid formulations, but monitoring for specific contaminants

in the field is not viable. Instead, SRBC focused on monitoring

parameters that would indicate a likely spill of either a saline

solution or mineral-rich deep groundwater—temperature, conductance,

pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), and turbidity. Monitoring

those parameters as well as water level can also yield insight

on other phenomena such as acid rain or turbidity from storm

events, Gavin notes.

The Commission chose three types of monitoring sites, says

Gavin—streams close to existing wells or truck routes, reaches

where infrastructure and other conditions make it likely that

wells will be established nearby, and more pristine streams in

highly forested areas outside the expected drilling zones. Some

stations also monitor high-value watersheds such as municipal

water supplies or popular recreation areas. To take full advantage

of the chance to gather new data on local watersheds, the network

sites are located in areas not already covered by U.S. Geological

Survey monitoring efforts

The range of locations should provide a useful combination

of baseline data, evidence of changes, and insight into local stream

systems that have not been well-studied in the past, says Gavin.

The size of the watershed connected to each site was a critical

decision.

“In looking at some of the critical criteria for choosing

locations, the question became, ‘what would be the most likely

volume of a wastewater spill, leak or breach we’d be dealing

with?’” Gavin notes.

Breaches or leaks from wastewater storage ponds near wells

present a significant water quality threat. But smaller spills can

also be a problem. For instance, an average tanker truck carries

5,000 gallons. A spill of that size could easily be diluted in

a large watershed, or get flushed past a monitoring station so

quickly that it would be missed if the network protocols weren’t

established properly.

“We conducted bench tests with YSI equipment in the lab

A593 0811

Y S I Environmental Pure Data for a Healthy Planet.® Application Note

and simulated frac wastewater,” says Gavin. “We determined that

if we targeted watersheds no greater than 60 to 80 square miles,

they generally have flows where we could detect changes in water

quality if wastewater was introduced into the stream.” Most of

the monitored streams run below 100 cubic feet per second (cfs)

80 to 90 percent of the time, and flow in the single digits or teens

during low-flow conditions.

“We have all of our stations taking observations every five

minutes,” Gavin adds. “It goes back to what we defined as our

most probable scenario—a volume of 5,000 gallons carried in

a truck. With a plume of that concentration, we could detect at

least some part of it—the beginning, middle or end—within a

five-minute interval.”

If key parameters surpass normal levels, the station triggers

an alarm to prompt an investigation.

The system was put to the test in May 2010 when a wastewater

pit liner breached, releasing frac flowback water near Bob’s Creek

in western Pennsylvania. The drilling company reported the

breach to state officials, and SRBC paid special attention to data

coming from a sonde seven to eight miles downstream of the spill.

“We were pleased that it wasn’t a large volume, but we were

able to see a distinctive breakthrough curve,” Gavin says. You

could see the rise in conductance for about 24 hours, then the

fall as it moved through the system. In that sense, we had a little

test to see if we could pick up an event.”

Logistical Considerations

Some logistical considerations also have to be taken into account.

For instance, notes Gavin, stations must be situated so the

monitoring instruments stay submerged even during low-flow

conditions, and can be placed deep enough to stay below the

ice during the winter. The channel should also provide enough

flow to prevent leaves and sediment from building up around

the sonde, he adds.

Access is another big logistical concern. SRBC has built its

monitoring stations on both public and private land. Each has

its benefits and challenges.

Siting a station on public land is a simple matter of coordinating

with whichever state agency controls the property, though

Gavin notes that some state-owned areas were a bit too public,

raising concerns about vandalism in areas with heavier traffic.

Stations on private land can be more secure, but working with

landowners can have its challenges.

“You have to have private landowners agree to participate,”

notes Beauduy. “Several landowners stepped up immediately.

Others were concerned about the stations being near them, or

didn’t want people coming across their property.”

Reliability is Key

Every six to eight weeks, SRBC staff visit each monitoring

station to rotate the sonde with a lab-calibrated replacement, conduct

field calibration for the replacement instrument, and bring

the long-deployed sonde back to the lab for calibration, cleaning

and QA/QC before it’s redeployed at another station. Durability

and stability are key to making the system work smoothly.

“The YSI sondes have been very reliable, with even lower

maintenance needs than expected,” Gavin says. “They’re very

versatile and durable for field deployment. I was familiar with YSI

products from when I worked for USGS back in the early ‘90s,

and we had quite a comfort level with the company’s sondes from

our drinking water monitoring system back in 2003.”

During the regular maintenance visits, technicians also collect

water samples to be lab-tested for pH, chloride, barium, total

dissolved solids (TDS), sulfate and total organic carbon (TOC)

after each visit. Four times a year, water samples are collected

for a detailed analysis including calcium, magnesium, sodium,

potassium, nitrate, carbonate and bicarbonate alkalinity, carbon

dioxide, bromide, strontium, lithium, and gross alpha and beta—

a thorough workup that better characterizes the influence of

groundwater in the stream or indicates the presence or absence

of flowback wastewater. While on-site, the team also uses SonTek

FlowTrackers to measure stream flow.

Fresh Data ’Round the Clock

The sondes collect observations on a five-minute interval,

and transmit collected data to SRBC’s office every two to four

hours. Data is imported into SRBC’s database and within a few

minutes is posted without correction (and labeled “provisional”)

for public access at http://mdw.srbc.net/remotewaterquality/.

A year after the first stations went online, says Gavin, “we’re

at 10 million observations, but even at that level, the file size isn’t

that great. Analysis work is generating four-hour averages or

daily averages, and we’ll be running through corrections based

on calibration drift.”

After compiling the first year’s data, SRBC is getting ready

to release its first data summary. Gavin notes that more data will

be required to determine if and how fracking is affecting water

quality in the basin. However, a preliminary analysis shows great

baseline data for the station sites, and unexpected results from

some areas are prompting further study, he says.

“Some stations we’re keeping a closer eye on because of the

way the trends are—it may take more analysis to understand

what’s going on,” Gavin explains. “We’re also collecting supplemental

data on geochemistry—water samples for lab analyses—to

help characterize the natural conditions and put the continuous

data into context.”

A broad array of users has accessed the data. “We have everybody

from just your private citizen to locals who are part of

civic or watershed groups to those more specific citizen groups

organized around Marcellus,” says Gavin. “The state uses it as well

to keep an eye on conditions. The industry itself has been watching

the data. And there’s been a lot of interest from universities.”

The Commission posts a glossary of key water quality terms

and explanations on its web site, though Gavin says most visitors

to the network’s web site are familiar with water quality concepts

and what the data means.

Real-time data, long-term trend monitoring and spill

alarms will all be important in monitoring surface water in the

Susquehanna River Basin’s Marcellus shale region. But the ability

to collect long-term, continuous data and post it online for

the world to see takes the monitoring network to an even higher

level, says Beauduy.

“This is a way to provide value-added service to our member

commissions, especially on something that’s somewhat controversial,”

he says, “in a way that lets the science speak for itself and

lets the public have access to the data in a transparent manner.”

©2011 YSI Environmental +1 937 767 7241 Fax +1 937 767 9353 environmental@ysi.com www.ysi.com