The Northwestern filter changes color when full of carbon dioxide, then changes back after being emptied

As concerns continue to rise over man-made carbon dioxide entering the atmosphere, various groups of scientists have begun developing filters that could remove some or all of the CO2 content from smokestack emissions. Many of these sponge-like filters incorporate porous crystals known as metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). Unfortunately, most MOFs are derived from crude oil, plus some of them contain toxic heavy metals. Researchers from Illinois' Northwestern University, however, recently announced that their nontoxic MOF sponge - made from sugar, salt and alcohol - is fully capable of capturing and storing CO2. As an added bonus, should you be really hungry, you can eat the thing.

The main ingredient in the edible MOF is gamma-cyclodextrin, which is a biorenewable naturally-occurring sugar derived from corn starch. Metals taken from salts such as potassium benzoate and rubidium hydroxide hold the sugar molecules in place, those molecules' precise arrangement within the crystals being essential to the capture of CO2.

"It turns out that a fairly unexpected event occurs when you put that many sugars next to each other in an alkaline environment - they start reacting with carbon dioxide in a process akin to carbon fixation, which is how sugars are made in the first place," said postdoctoral fellow Jeremiah J. Gassensmith. "The reaction leads to the carbon dioxide being tightly bound inside the crystals, but we can still recover it at a later date very simply."

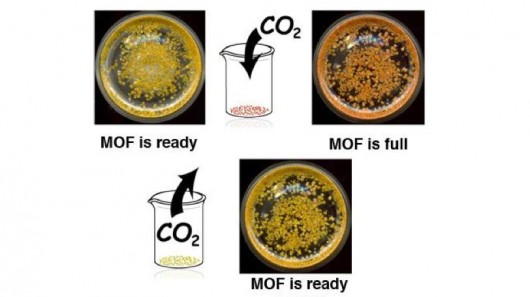

Not only can the filters be emptied of CO2 and reused, but they also have a way of letting people know when they can't hold any more. Each crystal has an indicator molecule placed inside of it, which changes color according to the surrounding pH. When the whole sponge changes from yellow to red, that means that it has reached capacity. After being emptied, its color returns to yellow.

The Northwestern research was recently published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

Copyright © gizmag 2003 - 2011 To subscribe or visit go to: http://www.gizmag.com